On Barbara

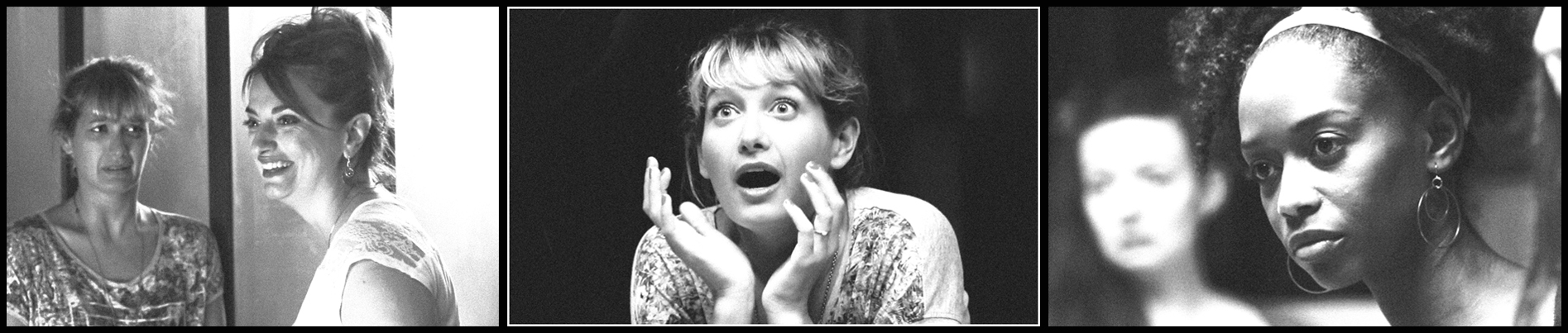

“Barbara,” written and directed by Yannick Privat, is a smart, beautifully shot, dialogue-rich short film of twenty minutes set in a single location, an apartment in Paris. Seven actresses are gathered in a living room discussing their prospects in the highly competitive film industry, each looking for her big break, in this case concretized by the imminent casting decision for the role of Barbara, the lead in a new Paul Thomas Anderson film.

The film begins somewhere in the middle of the evening, the actresses passing a joint, one of whom, Pauline, is complaining about an actress who’s not in the room: the type all of them know, she says, who positions herself right in front of the camera, blocking everyone else from view. This is a situation to which all of the actresses in the room can relate. Pauline says she’s come to terms with the idea that she won’t be cast as the young lead. Another of the actresses says, consolingly, even if that were true, she still has the chest for it. Nonetheless, one of the other characters says, she won’t get the role of Barbara. But neither will anyone else in the room, she adds. This type of commentary and dialogue sets the stage for a series of electric exchanges among the women that seem, even with the best of intentions, to constantly strike nerves, all of which adds up to a subtle and complex portrait of the industry and its competitiveness and the effect this has on the women, working actresses who seem to be mere steps away from the successes they covet.

The actresses lament a lack of compelling roles for women. Pauline is accused of having played “three whores.” In her defense, she says she’s played a variety of whores, each complex: the romantic whore, the nympho, the delicate whore, the tortured whore, the one “who owned it,” the one who didn’t and the one who didn’t quite own it. Another says, “We don’t do this job to be ugly, do we?”, pondering what role they themselves play in perpetuating the industry’s standards of beauty. The women poke fun at themselves, constantly, but stray remarks reignite the fire as they trade insults and jabs, each negotiating the subtleties of these critical assessments through their own qualifications of what art is, and which kind of roles are the most desirable, the most worthy of praise.

Why do these characters resort to such meanness, often disguised as comedy? (Or is it comedy disguised as meanness?) Sometimes, it’s to do with differing ideas about their own identities as they perceive them themselves, and as perceived by the others in and beyond the room. Sometimes, it may be to entertain the others, or to apply humor to what seems to be their shared prospects, or collective fears, in the face of an industry from which they feel, at least to a degree, cast out. The actresses replicate this pigeonholing, at times, in tune with the same prejudices. Yet, even as insulted as they seem to be by their friends’ jabs, they rebound quickly, they find humor, and part of the genius of Privat’s film is in filling the air with noise and contentiousness without giving the impression that this night will change the stakes or the nature of the friendship among the women. One woman, insulted by the claim that her accent sometimes makes her sound “a bit criminal,” a few moments later returns to the living room from off-screen, and confirms excitedly the rumors that the actress hosting the evening actually does have a TV in her toilets, perhaps also communicating that she’s moved on from the earlier insults. If she’s just discovering this, and the others didn’t know either, then perhaps the actresses aren’t as close as they sometimes appear to be. Some seem more intimately acquainted. Revelation after revelation, and jab after jab, sets the living room afire, and twenty minutes pass before you feel you’ve even had a chance to sit. The film’s final revelation, and what it leads to, further complicates and tests boundaries in Privat’s dark and highly comic satire, a deft and delicate masterwork, a study of contradictions and friendship and the artist’s struggle that is provocative, enlightening and rare.

—John M. Keller

Watch the film here.