A Visitation

of Skin

She said, it’s like you’re taking too big a mouthful of something you can’t get enough of. You’re chewing not to masticate it but to get as much into your mouth as you can. And pieces are falling out, shining and wet. These are the stories.

It was the fox, I recall, who told the Little Prince that words are the source of all misunderstandings. I didn’t agree with this statement at all, especially since it was itself made of words, and because it seemed to mean that we should all just shut up and let our flesh have its way. That’s terrible advice, I thought.

The fox was talking about a kind of taxidermy, a form of life whose appearance is outwardly preserved but inwardly replaced in every living respect by dead matter, by stuffing. He helped the Little Prince—himself a form of childhood preserved in the face of an adult world that seemed too complicated to process, that had to be broken down, reduced to something that seemed outside of words altogether—to understand how an individual is tended to (these were the fox’s words) in the particulars of a relationship, one in which that particular individual, or for that matter any living thing, is differentiated from any other person or living thing to which in most respects it’s identical. To move the skin, is what the word taxidermy means literally, and I thought about what I would look like if I were flayed and the pieces of my skin, formerly whole, stitched together to cover another body. Or not even another body, I thought, but some ligature of wire and cotton batting. What a creature I’d be, I thought, what a monster.

Which is it? I wondered. Is it that words wipe out the presumed uniqueness of an individual moment, the moment of intimacy, or do they allow us to preserve that moment, even as it becomes mobile, transformed by the act of preservation into something other than it once was, something singular, identical only to itself?

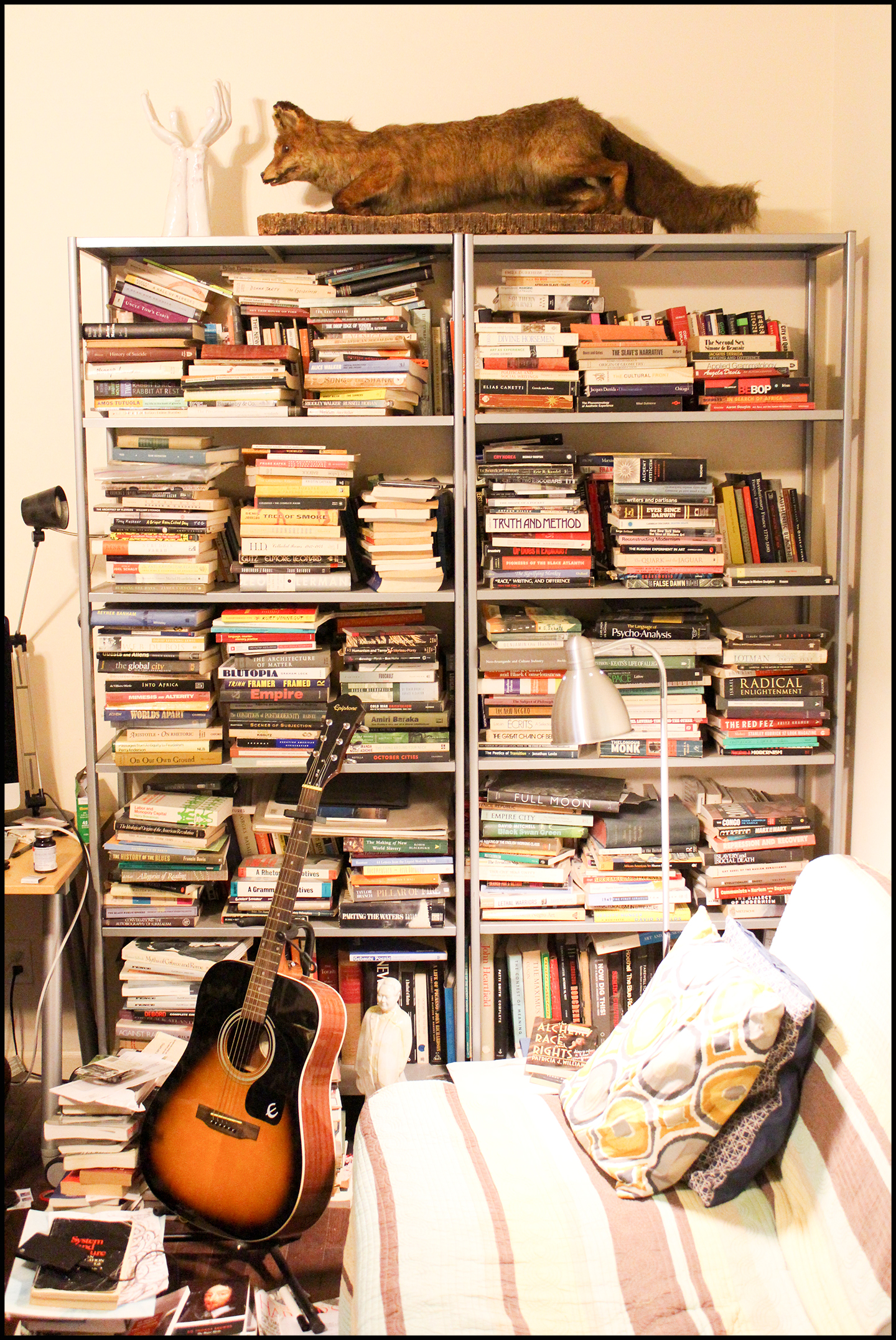

Fuck that guy, she said. She meant the Prince, I thought. I’m looking at the fox, mounted and sitting on top of a bookshelf in my apartment. Its hind legs are slightly more extended than those in front, body crouched, tail trailing the ground, glass eyes looking at whatever has surprised it. On top of the bookshelf, as it is, silent and inert, it’s entirely without context, which I suppose is a kind of freedom. Its mouth is in a strange position that I could interpret as either a snarl or a smile. It had been moving quickly but without fear through the undergrowth of the Franconian forest, hunting perhaps, or at that hour returning to its lair from a night of hunting. The Frankenwald, is what she actually said, and I knew exactly what she meant. She was still and silent, upwind of the creature. She pivoted on her toes, left leg forward, slightly bent at the knee, right leg straight and foot firmly planted behind, the bow bent and arrow notched, when she heard the fern rustling. Dark as it was under the sun-speckled leaves, the darkness of a permanent nocturne, she could spot the fox’s red-brown coat. But at that point, her own nerves wound tight as the cables of the compound bow, she didn’t have time properly to process what she was seeing. In that sliver of an instant she took the fox for one of the wild boar she was actually hunting, that she was hunting to feed herself and her daughter, and she simply fired.

Simply means reflexively, the unchecked trip of neural circuitry and her muscle memory, hand-eye coordination, the body absolutely certain of its position in space and time, and the arrow flies. Our senses move faster than we do. She realized almost immediately what she’d done, which was to put the arrow through the fox’s neck with a force that pinned it against a trunk. The arrow took the fox right off its feet. The body was still quivering when she got to it, its eyes just turning over into the fogged glass that they would literally become at the hands of the taxidermist. Eyes made to be looked at but not to see. To move the skin, as the word says, which in this case meant that she removed the arrow and the body suspended from it, by its neck, and the arrow from the body, the body surprisingly large as she stretched it out on a bed of moss and crushed fern. Ja, she said in slow Franconian, I felt terrible. The jaws of the fox with their tiny, razor-sharp teeth were still moving, still snarling and smiling, in response to the same reflexes, the same muscle memory, that her own body had used to fire the arrow. The chain of events starts further back than that, of course.

We were hungry before we were born, she told me. This was over a beer in the back garden of a bar that at the time, the city under siege from within by the forces of development, resembled an aid station for the dispossessed. The neighborhood was an intersection of Bangladesh, the Eastern Pale, and various West Indian diasporas. There was much other mortar amongst these major bricks, our own included. I was a refugee from northern New England; she was from a region claimed in its largest part by the Free State of Bavaria. Insofar as we’re both refugees, we’re likeminded, but in that place our very presence signified destruction, a force that gradually and suddenly would drive out what had preceded it. Her story reminded me of the killing of the last wolf in Extremadura, Spain, a story I’d read over and over during the five days I’d spent on a train from Irkutsk to Moscow, through endless loops of Siberian taiga, a landscape entirely white except for the pine trunks and the wooden villages that flickered past through the storm, because I had nothing else in English to read. The story was a lifeline to my own dispossession. In every respect this was a true story, which is to say it was real, that it matched the evidence of the senses, but it too reminded me of someone trying to force too much food into his mouth so that bits and pieces dropped out, shining and wet. In this story—the story of the killing of the last wolf in Extremadura—it was the wolf that was mounted instead of a fox, its body preserved inside a glass vitrine in the cottage of the man who shot it, like something you’d see in a museum of natural history, which the forester’s cottage most certainly was not.

Undeniably a wolf, a physical thing resting there on its own legs, but that certainty, that mark of authenticity, seemed somehow to apply also to the story itself, the story told by the man who had killed it—asesinato was the word used by someone else in the story to describe the later killing of another, different wolf, the one that gave the lie to the fact of the first being the last of its kind in that region of Spain, a barren plain on the frontier with Portugal, a place where only traces remained of what preceded it, which was poverty and joblessness—to a writer who continuously denied himself that status, blasting out the foundation of his privilege, each story within that story of the killing of the last wolf in Extremadura wiping out the truth of the story that had come before, each dead wolf replaced by another that had in fact been killed more recently, each story simultaneously a seed of doubt and an affirmation of authenticity, of hope, each story strung on a thread and displaced by the next like prayer beads clicking round and round between thumb and forefinger, calloused and browned by the sun. Murder, is what the man meant when he used the word asesinato, a word the character telling the story had the interpreter repeat in its original Spanish several times, to her annoyance, so he could understand exactly what the man who used it had meant.

It was impossible for me to know whether it was this fact of words and the stories into which they are made—whether these were the source of or answer to all uncertainty, I could not say—or simply the mounted fox that reminded me of the earlier story, the story I’d read over and over, stretched out in my narrow berth on the Transsiberian as snow whispered continuously against the night-black window in which the tiny flashlight by which I read was floating like an island. Probably the only way to sort that out is to do exactly what I’m doing, which is to tell this story, another story, which is to make more words that in turn will be either the source of or answer to all misunderstandings. What do the words preserve? is what I’m asking. To move the skin, I mean. This was precisely the question or problem I was not considering but rather experiencing at the moment in the bar’s dim garden in the hours after daylight had disappeared, spring just coming on after a winter I’d spent suspended in the utopia or no place of travel.

I set two fresh beers down and she said again, Fuck that guy. Gradually I realized that this wasn’t the Prince at all—a condemnation I was happy to agree with—but the father of her daughter, the daughter for whom she’d been hunting wild boar in the forests of Franconia, the forests surrounding the city of Bamberg, where she lived, a city built on seven hills. The daughter who, further, is now herself the mother of a daughter, making my friend, barely fifty (and you’d hardly know that from looking at her), a grandmother. The Franconian Forest, she told me, represents a link between the Fichtelgebirge and the Thuringian Forest, whose name alone made me imagine I was listening to some otherworldly, Edgar Rice Burroughs-type shit, an underworld that was truly, literally, under this world. To quote another source, the forest tops a broad, wooded plateau, running almost thirty miles in a northwesterly direction, sloping gently to the north and east toward the Saale River but dropping precipitously into the Bavarian plain to its west.

He didn’t tend to me, is what I gradually realized she was saying. Or maybe it was, he didn’t intend this to happen to me. The acoustics of the bar’s garden, I’ve come to realize, played tricks like that, confusing desire with intention, or maybe it was scorn with futility. I had seen both these emotions on the faces I passed in the streets of our neighborhood, in the silent ways their eyes looked at me. I could see them on the frozen face of the fox, crouched on the bookshelf as the rest of my apartment turned, for the moment I was looking at it, into the nocturnal underworld of the Frankenwald.

It was in this conversation that Elsie—which naturally is her name, I could hardly make something like that up—first told me the story of the fox, which in fact wasn’t one story but many, the most recent of which is how, desperate to make rent, she asked me to buy it. By it I mean that transitioned skin, teeth, claws, less a creature than a construction. She worked as a security guard at The New Museum, standing all day at her post in the second-floor galleries and telling people with her slow Franconian accent to step away from the painting or not to touch the glass or that photographs were permitted only without flash. I imagine a few of those tourists got off on the experience. That accent alone gave her size, stature, authority. Like most museum guards I’ve known, and there have been a few, she had nothing but contempt for the public, but I realized pretty quickly that she hardly thought anything more of the art itself. If she thought the people were German, either because of the way they looked—and the first time I laid eyes on her I knew right away where she’d come from—or because they spoke in German or spoke English with a German accent, then she addressed them in her native tongue.

Ja, she said, always this amazes them. I can imagine, I replied. I’d been to the museum myself once, when she was working, for the big Richard Pettibon show, and I laughed out loud when I caught sight of her across the gallery. She was halfway offended but also went along with the laugh. She couldn’t have weighed more than ninety pounds soaking wet, as the saying goes, and that blue uniform seemed rather to shrink or diminish than to expand her authority, as it was intended to do. Still, the accent compensated. She took her half-hour break and we went out to smoke. She was trying at that time to get several weeks off so that she could return to Bamberg for Easter, which was also her granddaughter’s birthday. This would be her first visit home since she’d crossed the water, and the first time she’d meet her granddaughter. It turned out the Pettibone show was about to close—which was the sound of history being throttled and its scream abruptly cutting off—and her boss thought a leave would be possible. Standing in spring sun on the Bowery she told me about ordering all kinds of German candy to her apartment in Brooklyn, candy she could get nowhere in America and so resorted to ordering online. She was making a gigantic Easter basket for her granddaughter, a basket that would double as a birthday present. She showed me a picture of it on her phone; the handle of the straw basket, resting on the floor, nearly reached her chest.

I don’t get it, I said. You’re ordering candy that has to be shipped here from Germany, just to take it back through TSA and that whole flight home, back to the very place it came from. Why don’t you just take the empty basket with you, or even just buy a basket in Bamberg, and assemble it there?

Noooo, she said with rounded mouth, her face hollow and haggard with worry. If my boss approves the time I’ll get there on Easter day, in the evening.

She shrugged.

I would have no time. I want to give it to her when I arrive.

I told her that made sense. It was after her return that she continued telling me about the fox, about what it had been, how it had happened, what it could mean.

She told me about it because she told me first about her compound bows. She had three of them, of varying sizes. She’d brought them with her when she moved to the States seven years before, I think as part of some failed relationship, but had broken them down to their components in order to get them into the country. Individually the parts mean nothing; assembled they possess a deadly force. As the name implies, each bow is a compound of components: there’s the middle section, the grip, with the riser and sight window and stabilizer bushing. There’s the top limb with the top cam and axel, secured by screw to the grip. There’s the bottom limb and bottom cam and axel, also secured by screw. Before the bow’s components can be assembled, the cable must be run through the cams and around the axels, distinguishing the bow string itself from the buss cable and the control cable, which while separate in name actually form a single line that loops like a figure eight between the cams, a figure that goes on and on without stopping. Anyway, she needed help assembling and stringing the bows, so she called me.

I’m not sure what she intended to do with the bows once they were ready. Maybe actually try hunting again, which given her economic situation after returning from the two weeks in Bamberg with her family was probably more a matter of necessity than nostalgia. She was totally broke. I imagined her small, black-clad figure, running on its toes along the sidewalks, hugging the brick walls and using parked cars for cover. It was then that she told me about killing the fox, about what actually happened that day, that early morning in the Frankenwald. The fox wasn’t the last thing she’d killed. That had been a small boar she took down about six months before she left for the States, but it was the fox that had affected her the most. I was securing the limbs of the largest bow, which was painted forest camouflage, adjusting the bolt and locking down the screw. It was a partisan’s weapon, I thought, and imagined the hunter being hunted through undergrowth. She had arranged the cable, threading it through the cams and securing its control posts, but after the limbs were locked down the bow had to be flexed to finish stringing it, which required the application of some considerable pressure or weight, weight that she herself lacked. This was mainly what she needed me for, as muscle, as she herself put it, cackling, which is certainly the first and probably the only time in my life this would happen to me.

Maybe it was the precise, mechanical quality of the work, I don’t know, or the steady pressure I was applying on something that might suddenly fly apart with considerable, even deadly force, but as I bent over the bow everything seemed to narrow into a cone around her voice, like her voice or the story that she was telling was deep in a summer lake in which I floated, looking down into the shafts of light, at the illusionary point on which they all seemed to converge. I remembered a single point of light in the dark square of the sleeper car’s window, groaning through the Siberian night. She was telling me, I think, about returning to the forest where she used to hunt, this time with her daughter and granddaughter, her daughter driving them to the trailhead, the three of them making their way into the early twilight along an overgrown path, a path that probably hadn’t been used in over seven years. They saw no one else on their walk. On all sides, Elsie said, she could hear the rustle and scrape of small creatures in the twilight, the hours of work for all the nocturnal creatures that populate the Frankenwald, including the boars that had been her prey. Her granddaughter was barely old enough to walk and so understood nothing, and her daughter seemed distant and uninterested in returning to old emotional ground, to the hunger that to her was most vivid now, in its absence, as evidence of the shameful grayness of poverty from which she’d escaped.

It was late afternoon in the bar’s garden, the place where Elsie had asked me to meet her, which as usual at that hour was mostly deserted except for the most desperate or familiar. Stringing the cables while applying pressure to flex the bow is difficult. Difficult and, as I said, dangerous, which is why a bow is generally strung on a press rather than by hand. The risk is that you slip or release the flexed limbs inadvertently or fail to secure the string or cables, unleashing hundreds of pounds of pressure at once.

Concentrate, I told myself, concentrate.

In any case, we were able to string only the largest, the one that she thought would be the most difficult. Difficult as it was, the medium and smallest were impossible, and finally we gave up. She stood in the fading light of the garden, surrounded by the exterior walls of buildings on every side, walls that to us, bent to our work, formed an interior, a space secure even from the now-eclipsed sun, and drew back the bowstring. It took her three or four tries to bend the bow, as she called it, which was a full draw, the limbs flexed as far as they could go. Left leg forward, slightly bent, right leg extended straight behind, foot firmly planted. From this position, the arrow had maximum force and accuracy upon release. She said this mechanically, as if she were reading from a manual. After we had finished stringing the largest bow and given up on the other two, she chuckled, rubbing her shoulder as we clicked glasses. This is when she offered to sell me the fox.

I would leave the village early in the morning, she told me. I’m not sure whether she did so because this was the best time to catch the night creatures, when they are slowest to react, dazed by the sunlight and exhausted by their wanderings. It might be because I really didn’t want to see anyone from the village, she said. Or not the village, she emphasized, but the edge of the city, of Bamberg.

Not the suburbs, no, she said, shaking her head. It is a village that was just swallowed up by the city. This is where my parents were from, this same place, for generations, since before the war. Ja, she said, it’s Bavaria, you understand? I was unemployed at this time and I had no choice, really, either to move back there or to do what I was able to do—what I had to do—because I had moved back there. I am a hunter, she said, rocking the bow in her lap. Ich bin ein Jäger.

It was at this moment that I realized that the concentration I’d had as I flexed the bow and we strung it had only deepened since we finished the one and failed at the others. It had nothing whatsoever to do with the physical pressure I’d applied on those carbon-fiber components, a pressure the cable then held in suspension. Fuck that guy, I whispered, by which I meant both the Little Prince and the fox that sold him that puerile shit about words being the source of all misunderstandings. Her voice had a steady, measured rhythm to it, the rhythm of someone taking great care to use a language that covered only part of her life, that she did not confuse with the physical objects it referred to, and even less with the universe of which those things are parts. Sometimes she would stop and describe something to me, naming it by its German name, and I would help her find the best substitute. We were not getting farther away from things, we were getting more deeply into them, under their skin, to the point that the whole fabric that was both made of those things and camouflaged by it vibrated with sound. I could have that fabric precisely as I could have it, which is in the words themselves and what those words did to my head, a head that had done its best and failed miserably to encompass Siberia, and before Siberia Mongolia, and before Mongolia China, and before China Korea. The war I was looking for had never happened, peeling back layer after layer. My career as a reporter, I realized, was finished. The only relevance here is the telescoping distance, a telescope that as I imagined it was more like one of those pirate spyglasses made of sections that can be collapsed for storage or extended for use. Snap a line to the horizon. The story, as she told it, drew one section from another, bent the bow as far as it could go, put into a small circle of clarity exactly what I’d tried and failed to understand about my winter from the beginning.

Ja, she said, fuck that guy. I had nothing, and I was living there in that shitty village, a village from which I inherited everything and nothing, no money even for a beer or smoke, and so what am I going to do. I had this, she said, patting the bow, although this is not the one, it was another one—one that she would show me mounted on the wall of her apartment when, maybe a week later, I went to pick up the fox, which she’d wrapped completely in heavy-gauge garbage bags she scored from her super, and carry it home through the streets of the city—that I hunted with. I knew I could do it, although I had never done it. I had shot only targets, she said, miming the action of bending the bow and releasing the string. The note it made rang off the brick and concrete block that surrounded us.

She shrugged. So this is what I did, ja? I would leave the apartment in the early morning when my sister could watch my daughter. I would walk from the street of the village to the road that the street became in the east, and walk east on the road to the forest. There, in the field before the forest actually began, a field where there once were cows but now only grass, the pavement would end. First there were two, what do you call them—she’s making parallel lines with her index and middle finger, like either a peace sign or a small claw in the air—tracks, and after the tracks there is only one path for the feet. Already you are in the forest. Ja, it is darker there, not quite night again, but going back in time, a time when the moon was still rising. It is mostly stone, the floor, with what do you call it, moss on the stone and small bushes, ferns and things. You have to be careful once you leave the path, you must place your feet very carefully. I would walk maybe a mile into the forest, away from the pavement and the last houses, where there is less fear in the animals. I liked this very much, being there at that time, so far from the houses, from the windows of the houses, from the eyes. I was nothing for them but my mother’s daughter, failed out of everything, pregnant and moving home. And that fucking guy, he did nothing. So it was just me and my daughter in that apartment, and every five or six months, when we were hungry enough, I would go out into the forest again.

She cackled, saying this, rocking the bow in her lap, her long braids dark and shining, flecked with gray, silver jewelry like a yoke around her neck, her hands moving quickly from thing to thing. Ja, I don’t eat so much, and my daughter, she is so little at this time. But, she said, getting serious again, her gaunt face bending to the lighter’s flame, I really liked those times in the forest. It would be very quiet and I would be wearing these very soft boots, boots with very soft soles, boots I sewed myself from scraps of leather, and I was making no noise. Only in that silence can you actually hear. Our time, this time, tapping her bare wrist, it doesn’t matter anymore. Then you become all ears, everything is sound, it doesn’t matter what you can see. Mostly I would stand and wait where I can find, what’s the word, traces of where the boar are moving. The eyes get in the way there, when you are hunting in that twilight, that dusk around dawn, and all you need to do is listen. This goes a lot farther than seeing. You can imagine the whole space of that forest, all the space that you can hear, in your head, the way the wind is making that noise and moving in this direction or that, and the smallest sounds of the dried leaves and grasses that are the squirrels or some other small creatures, individual ones moving in different directions, at different distances, and maybe some hares—you say hares, yes, or rabbits?—making larger noises and above them, just above them, are the wild boars.

No, she said, shocked that I would even ask, I never hunted deer. I love deer. I could never hurt them. Sometimes I would see them in the forest, they are so beautiful. No, it was the boar I was hunting for the meat to feed myself and my little girl. And ja, that would be it. It wasn’t difficult. I would find the traces and I would wait, and I would shoot. Like I said, you just have to listen, it doesn’t matter what you can see.

Unless you’re the fox, I said. Then it matters.

She cackled. Ah, that’s right, you got me.

It was a misunderstanding, she said, her face sobering again, its hollows deepening in the growing darkness. Exactly, I said. I felt terrible, she said, but in that word were many things that remained to be said out loud, one of which was the look on the fox’s face, a snarl or a smile, the posture of its body at the precise moment Elsie released the arrow, every particular thing vibrating suddenly on the string, the cables, understanding in that slice of an instant that while everything is continuous, there is an end. Asesinato, I thought, which means murder. I thought of the pieces, wet and shining, dropping from the fox’s mouth. She said, no, I didn’t clean them, the boars. A friend would do that for me later, and we would split the meat. I cannot do this myself. This same friend, he did the taxidermy. I would remove the arrow and clean it and my hands and wrap the wound with cloth so it wouldn’t bleed on me, and then I would put the animal over my shoulders—she’s tracing her narrow figure as she says this, her shoulders and upper arms and chest outlining a presence that hovered over or around her physical body, the second skin of what she’d killed—and tie its legs together. I would walk out of the forest with it like that, the light usually well up by now so I would come gradually to the part I hated most, returning to the village, from trees to field to houses, from one track to two, like I was coming up from some world underneath, back to the present, the paved road to the street, and the people tending to their business there, each to his own, which was not mine.

She paused. You can’t imagine how far away they seemed, she said. They wouldn’t say anything at all, they were silent, they would just look at me.♦