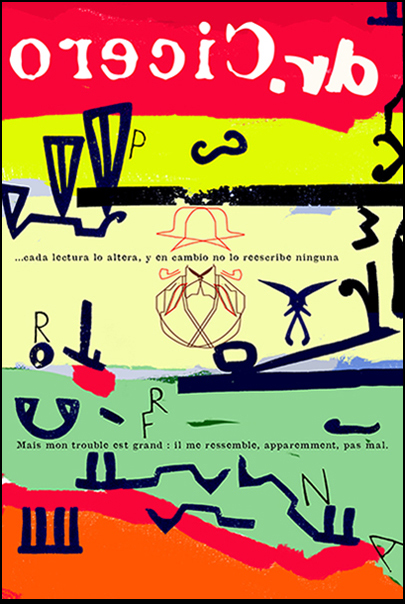

Dr. Cicero seeks original work that does not fit into obvious categories. We are looking for stories, short screenplays, artwork, etc. that sound different,

or that fashion out of the same ink and paper—or their digital equivalents—something fresh. Sometimes, in this age of globalization, we could almost

imagine the entire world is doing the exact same thing at the same time, talking about the same thing and the same people, reading the same books and watching the

same films and television. The force of this pull is so strong as to be irresistible, causing anything else that might otherwise have seized our attention to disappear

from view, even as it still very much exists.

Where does one look? And how can we avoid the distractions that prevent us from seeing something different?

Recently, visiting the Museo Casa de la Memoria (The Museum of Memory) in Medellín (with whom we have collaborated in this issue), we were impressed by how

they refrained from mentioning the city’s greatest villains, even though much of the sorrow they record inside their walls could be directly linked to them.

It occurred to us that we could create a publication that also sometimes omitted important names and places and things linked to the present moment and present trends,

and that we could aim to become a forum for the kind of work that goes beyond the topical and stands outside of time. And we could actively seek out the kind of material

that captures the spirit of the times in a language or gaze that may be something we associate more with that of another time, or something new altogether.

This

is not to say that we intend to be irrelevant, and to disregard the present. Our first edition contains an interview with Javier Marías, whose narrative gaze is

distinct from that of his contemporaries, and yet few writers today could be writing more relevantly. Marías may even have found an equation that fits perfectly

with our present time: sometimes the pacing and mystery seem to usher the reader forward with astonishing speed, while long meditations exist entirely outside of time,

and carry their own separate rhythm, and weight. Marías’ work is completely without equal in form or content, and his voice is one of the most singular in

literature today, even as what he says carries truths and grains of truth that resonate universally.

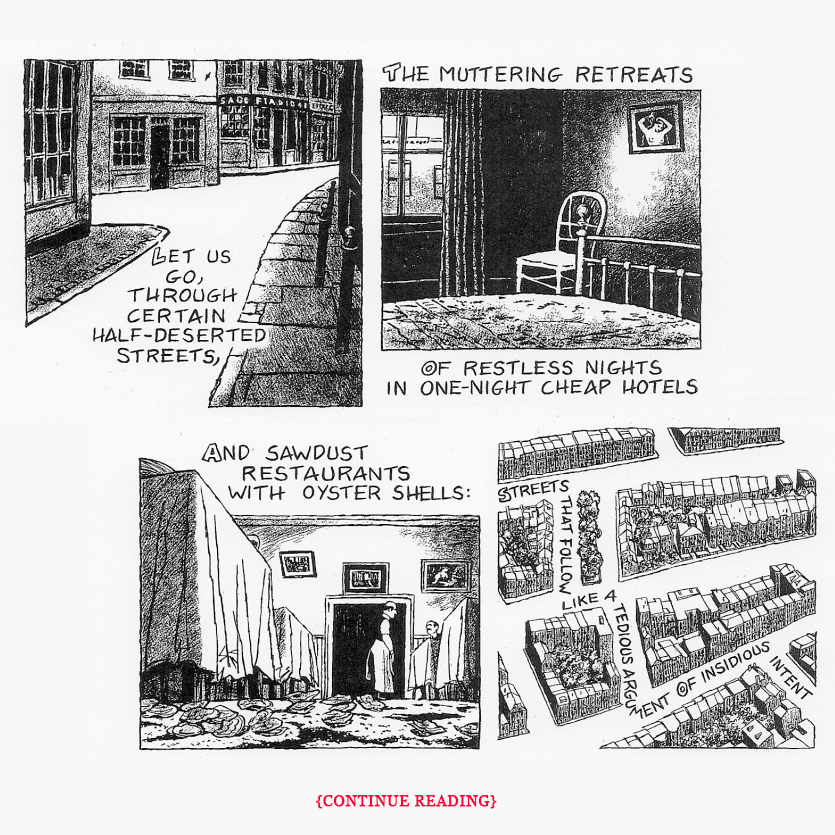

The work of T.S. Eliot regularly reappears in

Marías’ work; in Berta Isla, his most recently published novel, the characters quote from Eliot’s poems. The phrase, “In short, I was

afraid” (from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”) appears in his Your Face Tomorrow series, and again in Berta Isla. While J. Alfred

Prufrock, the presumed speaker of the poem, fears his better days are behind him, the poem itself will never grow old, not as long as it is remembered. Its lyrics and

rhythm articulate and enfold so many sentiments and ideas that, without them, we might feel our depth of understanding has been reduced. This issue includes an

illustrated version of the poem, and a prose adaptation. The pages dedicated to the poem here are a reminder of the work of the past that has reinvented and recast

language, and under whose spell we write, work that we cannot forget because its rhythms and sentiments have become encoded in our language. Such works encourage a

conversation among artists, dead and alive, and their audiences, forging a continuum that reaches beyond the present moment to the generations that lived before us,

sometimes centuries ago, in these very streets, and debated with fervor issues that, while the names and dates are different, resemble ours.

True original work

is a subjective concept. Recently, Dave Chappelle quoted Miles Davis, who said, “Sometimes you have to play a long time to be able to play like yourself.”

This is part of it. Another is resisting the lulling trance of other voices, ideas, and trends, especially those that characterize one’s own time period. Chappelle,

in the same speech, alluding to a climate in which ideas, especially original and controversial ideas, are increasingly under attack, defended his genre (stand-up comedy)

and its “true practitioners” and the range of ideas that emerge from a genre that by its very nature challenges the boundaries of comfort and offense:

“There’s something so true about this genre—when done correctly—that I will fight anybody that gets in a true practitioner of this art form’s

way...I’m not talking about the content, I’m talking about the art form.”

Dr. Cicero is an ambition; it is a pursuit, an idea, an intention.

We intend to be a 21st century publication with a more timeless gaze; we aim to intentionally court the kinds of texts that go beyond current events, and we aim to publish

writers regardless of celebrity, regardless of the biographical or the trendy, aiming to discover work that is great in and of itself. We aim to celebrate language and

originality and reject the mechanisms that, through classification, confine artworks, often seeking to view them through prisms foreign to the work themselves, including

those things over which artists have little or no control. It is through art that we may escape our physical identities, to enter another plane where rules that would

otherwise restrict us do not apply. There, we belong to something else, perhaps even something of our own choosing. As Roberto Bolaño said, “My only patria

[fatherland] is my two children...And perhaps, secondarily, certain moments, certain streets, certain faces or scenes or books that are inside me and that someday I will

forget...”

-The Editors

Dr. Cicero seeks original work that does not fit into obvious categories. We are looking for stories, short screenplays, artwork, etc. that sound different,

or that fashion out of the same ink and paper—or their digital equivalents—something fresh. Sometimes, in this age of globalization, we could almost

imagine the entire world is doing the exact same thing at the same time, talking about the same thing and the same people, reading the same books and watching the

same films and television. The force of this pull is so strong as to be irresistible, causing anything else that might otherwise have seized our attention to disappear

from view, even as it still very much exists.

Where does one look? And how can we avoid the distractions that prevent us from seeing something different?

Recently, visiting the Museo Casa de la Memoria (The Museum of Memory) in Medellín (with whom we have collaborated in this issue), we were impressed by how

they refrained from mentioning the city’s greatest villains, even though much of the sorrow they record inside their walls could be directly linked to them.

It occurred to us that we could create a publication that also sometimes omitted important names and places and things linked to the present moment and present trends,

and that we could aim to become a forum for the kind of work that goes beyond the topical and stands outside of time. And we could actively seek out the kind of material

that captures the spirit of the times in a language or gaze that may be something we associate more with that of another time, or something new altogether.

This

is not to say that we intend to be irrelevant, and to disregard the present. Our first edition contains an interview with Javier Marías, whose narrative gaze is

distinct from that of his contemporaries, and yet few writers today could be writing more relevantly. Marías may even have found an equation that fits perfectly

with our present time: sometimes the pacing and mystery seem to usher the reader forward with astonishing speed, while long meditations exist entirely outside of time,

and carry their own separate rhythm, and weight. Marías’ work is completely without equal in form or content, and his voice is one of the most singular in

literature today, even as what he says carries truths and grains of truth that resonate universally.

The work of T.S. Eliot regularly reappears in

Marías’ work; in Berta Isla, his most recently published novel, the characters quote from Eliot’s poems. The phrase, “In short, I was

afraid” (from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”) appears in his Your Face Tomorrow series, and again in Berta Isla. While J. Alfred

Prufrock, the presumed speaker of the poem, fears his better days are behind him, the poem itself will never grow old, not as long as it is remembered. Its lyrics and

rhythm articulate and enfold so many sentiments and ideas that, without them, we might feel our depth of understanding has been reduced. This issue includes an

illustrated version of the poem, and a prose adaptation. The pages dedicated to the poem here are a reminder of the work of the past that has reinvented and recast

language, and under whose spell we write, work that we cannot forget because its rhythms and sentiments have become encoded in our language. Such works encourage a

conversation among artists, dead and alive, and their audiences, forging a continuum that reaches beyond the present moment to the generations that lived before us,

sometimes centuries ago, in these very streets, and debated with fervor issues that, while the names and dates are different, resemble ours.

True original work

is a subjective concept. Recently, Dave Chappelle quoted Miles Davis, who said, “Sometimes you have to play a long time to be able to play like yourself.”

This is part of it. Another is resisting the lulling trance of other voices, ideas, and trends, especially those that characterize one’s own time period. Chappelle,

in the same speech, alluding to a climate in which ideas, especially original and controversial ideas, are increasingly under attack, defended his genre (stand-up comedy)

and its “true practitioners” and the range of ideas that emerge from a genre that by its very nature challenges the boundaries of comfort and offense:

“There’s something so true about this genre—when done correctly—that I will fight anybody that gets in a true practitioner of this art form’s

way...I’m not talking about the content, I’m talking about the art form.”

Dr. Cicero is an ambition; it is a pursuit, an idea, an intention.

We intend to be a 21st century publication with a more timeless gaze; we aim to intentionally court the kinds of texts that go beyond current events, and we aim to publish

writers regardless of celebrity, regardless of the biographical or the trendy, aiming to discover work that is great in and of itself. We aim to celebrate language and

originality and reject the mechanisms that, through classification, confine artworks, often seeking to view them through prisms foreign to the work themselves, including

those things over which artists have little or no control. It is through art that we may escape our physical identities, to enter another plane where rules that would

otherwise restrict us do not apply. There, we belong to something else, perhaps even something of our own choosing. As Roberto Bolaño said, “My only patria

[fatherland] is my two children...And perhaps, secondarily, certain moments, certain streets, certain faces or scenes or books that are inside me and that someday I will

forget...”

-The Editors

|

INTERVIEW As an approach to this interview, I decided I would read all of Javier Marías’ published novels and short stories (just as much for an excuse to read them as fitting preparation for the interview). Moving from one book to the next, each felt like different neighborhoods of the same majestic city, one to which we long to return after we’ve left, where we recognize similarities in the streets and signs and the attentions of its inhabitants, even if the different topography (or subject matter) from book to book is evident. The first sentence frequently thrusts us right into the middle of a crisis, one that, for all its immediacy and urgency, can wait. We experience time differently. Or, rather, our time is replaced by his. Every book encloses within it a notion of time (or perhaps multiple notions of time). In Marías’ books, while intrigue carries the reader forward with urgency and speed (as we wonder how things will fit together, how a stain of blood on a banister will be explained, or why the man who accompanied a woman in her death and whose identity is not known has sought out... |

|

POETRY

Chrrr chrrrrreee |

|

|

|

|

PROSE

J. was lining up his coffee spoons. How many would he need to measure out

his days and ways? He was getting older, his head grown slightly bald, and

the women weren’t lining up at his doorstop as they had been (or so he

remembered it) some ten years before. |

|

|

EXCERPT

On my street—I write this in Paris, eight hundred kilometers higher up

on the map—there’s a burly chômeur with bleached

blond hair and a large motorcycle (Wow! look at that beast,

Clément says as we pass by), whose wife, an immense fake-blond chewing

gum and smoking a cigarette (I’ve seen her, I could swear, chewing and

smoking at the same time, which is rather impressive) is not, as one might

imagine, without a certain elegance, as demonstrated through such tender gestures

as when she crouches down over a stroller in order to wipe the face of her

snotty-nosed child. |

|

EXCERPT FROM THE MEMOIR

The man I called my father died in 2005, ten years after Maman Pauline. I am not

sure I ever really knew him. We were both intimate and distant. Intimate, because

I had always felt his eyes watching me, accompanying me every step of the way,

anxious I might stumble or fall, concerned I should choose the path he had opened

up for me. |

|

|

EXCERPT FROM THE MEMOIR

The photo’s in black and white, with a bit torn off at the

bottom, on the right-hand side. It was taken at the end of the 1970s,

one afternoon in the Joli-Soir district. |

|

NONFICTION

She said, it’s like you’re taking too big a mouthful of

something you can’t get enough of. You’re chewing not to

masticate it but to get as much into your mouth as you can. And pieces

are falling out, shining and wet. These are the stories. |

|

|

EXCERPT FROM THE NOVEL

Howling and half-naked in his torn and bloody clothing Fargo is a

desperate man and dangerous to himself and others. He ricochets

around his kitchen, heaving furniture into the street. The street

is twelve stories down and Fargo fills the New York air with chairs

and tables, lamps and dishes, cutting boards and cabinets, electric

fans and plastic caddies, frying pans and double boilers, brooms and

mops and metal buckets, canned goods and Pyrex platters, a garbage

can, a cookie jar, a toaster oven, even the refrigerator door, which

he rips off and throws out the window. |

|

FICTION I got on the plane (this after two hours or so in the airport: going through the security checkpoint, drinking a coffee because I was tired and needed to do some work while in transit, and buying some aspirin at a shop, for which I have a receipt with the name of the shop and the time I was there). The plane took off. It was a small one, the kind that makes you immediately think of plane crashes. At one point, I got up to use the bathroom, as I’d had a lot of water. Every time I’m on a plane I make a point of getting up at least once to use the bathroom to stretch my legs. I prefer window seats because I can watch as the world seems suddenly small, and then the cities are replaced by clouds. There by the window, you are generally sat next to two people, and some might say you are at their mercy should you need to use the bathroom, but I like asking them to move because, in a way, this is a small redistribution of power—I request that they get up; they must comply. (If you sit in the aisle, the circumstances under which you can ask two strangers to move are limited.) Mostly, I slept. I couldn’t work, and didn’t even pull the... |

|

|

AN IMPROMPTU

1. Beginners Please |

|

|

|

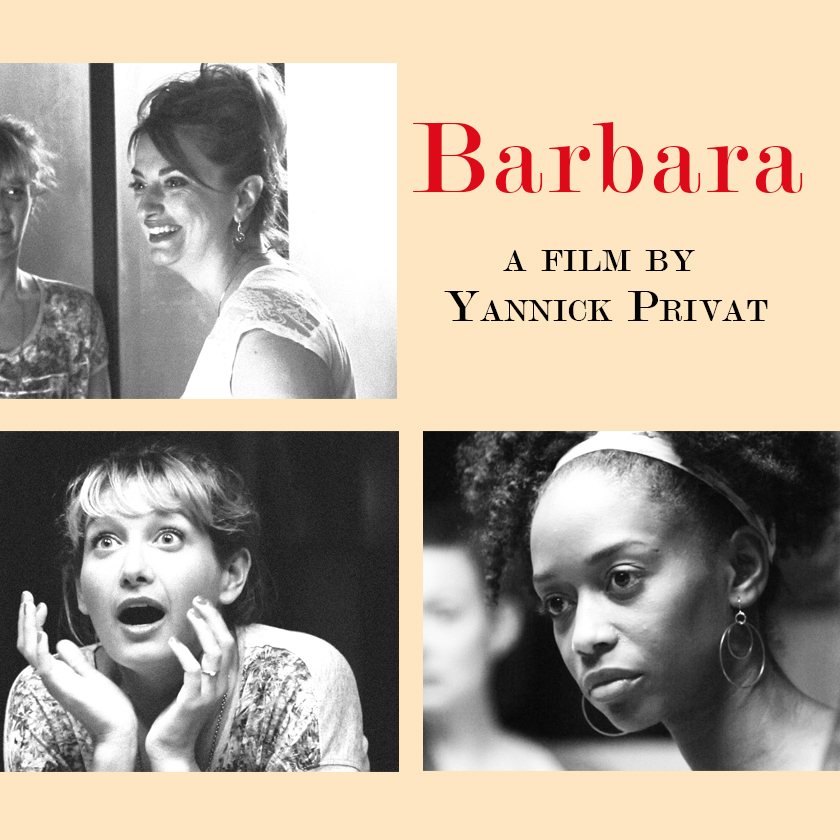

SHORT FILM

“Barbara,” written and directed by Yannick Privat, is a

smart, beautifully shot, dialogue-rich short film of twenty minutes

set in a single location, an apartment in Paris. Seven actresses are

gathered in a living room discussing their prospects in the highly

competitive film industry, each looking for her big break, in this

case concretized by the imminent casting decision for the role of

Barbara, the lead in a new Paul Thomas Anderson film. |

|

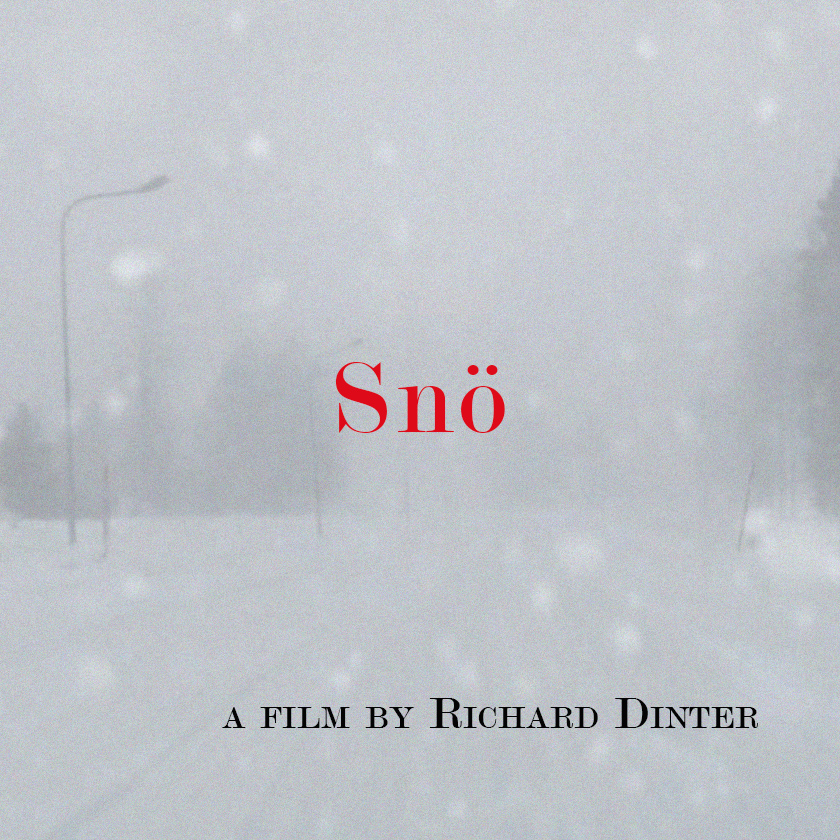

SHORT FILM

It was November, 1990. It’s afternoon,” the voice begins.

This follows a shot of snow falling against a gray sky, the flakes

appearing as black or negative flecks against the gray. The subject

speaks into the snow. And in that speaking, we find something of the

nature of memory, storytelling, and film: we don’t travel, in

remembering, from present to past, but rather the reverse. The past

becomes present. In doing so we move toward a self, a presence, through

depths that are camouflaged by the sensory world. This voice cannot

be said, here, to constitute a “voiceover” that, like the

caption of a photograph, is meant to complete the image, to reveal the

narrative phantom or ghostly subject that, even as it lies outside or

beyond the image, haunts it with meaning. |

|

Please send all submissions, in .doc, .docx, .rtf or .pdf form, to fiction@drcicerobooks.com.

In the body of your email, let us know where you saw this notice. In the subject line, please indicate

the nature of the submission, the name of the story and the author, in the following format:

SHORT SCREENPLAY SUBMISSION: Un Chien Andalou/Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí

In your cover letter, please do not list awards, previous publications, your age, country of origin,

gender or other biographical details.

We currently accept fiction, short screenplays, essays, art and black and white photography.

There are no length requirements, though we may not generally publish very short (flash) fiction.

We are a small staff, and cannot respond to all submissions. If you haven’t heard from us within three months,

please consider trying us again, with a different submission.

We don’t mind simultaneous submissions; if your story is accepted elsewhere, however, please let us know so

that we can withdraw your story from our reading pile.